Mimbres.

|

|

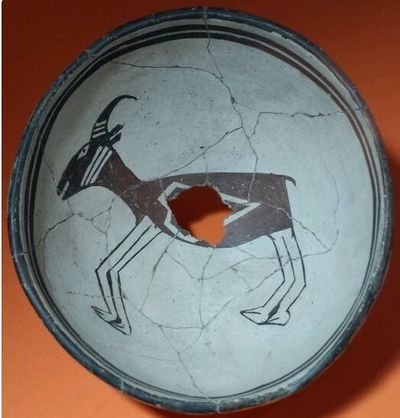

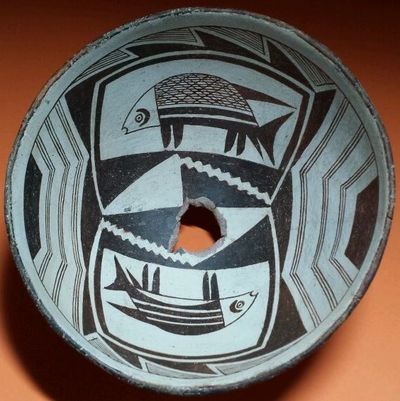

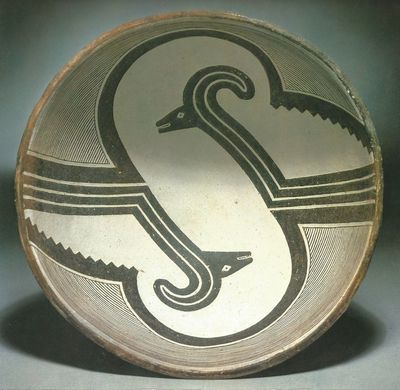

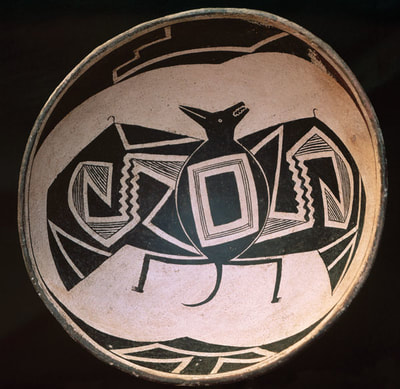

Condensed History:The Mimbres occupied the somewhat isolated mountain and river valleys of southwestern New Mexico from about 1000 to 1250 AD. Recognized as part of a larger group known as the Mogollon, the Mimbres were concentrated around the Mimbres River, named by early Spanish settlers for the abundance of mimbres or small willows found along its banks. The name Mimbres, or Mimbrenos, was adopted as the official name of the culture at the turn of the century. Known primarily for their exquisite painted pottery, the Mimbres culture is of interest to archaeologists and anthropologists, as well as art historians and collectors.

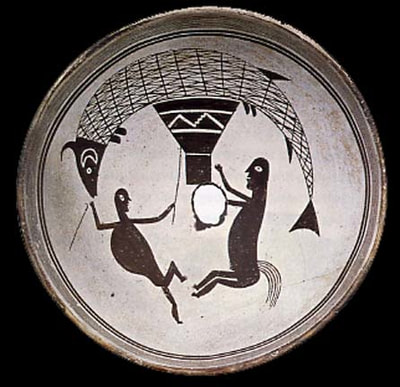

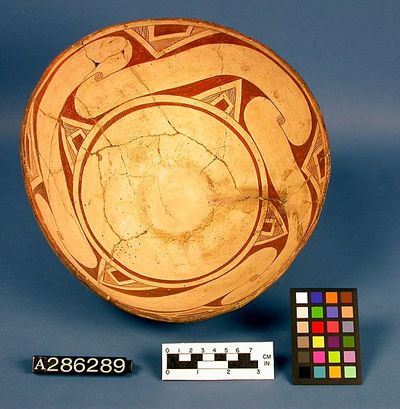

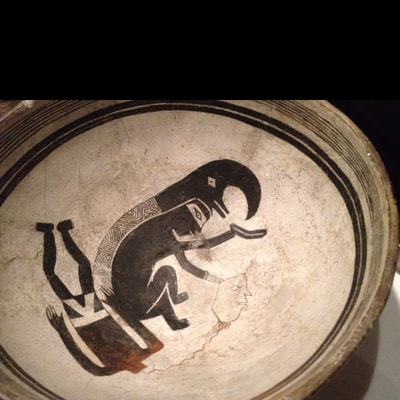

Contemporary research on the Mimbres culture relies heavily on comparisons with more modern Puebloan pottery and practices, as widespread commercial looting has destroyed many sites over the years (Hegmon 2002). According to such comparisons, as well as the presence of female burial sites complete with pottery-making tools, it is generally accepted that the artists responsible for creating the pottery were women, who received their training from relatives (Hegmon 2002). Although there are no maker’s marks on any of the pottery, Leblanc has argued that the most spectacular designs were created by one or a few painters. Research conducted by Leblanc and Ellis in 2001 suggests that a handful of potters making between 50 and 100 bowls a year could account for all Mimbres black-on-white ceramic production. If Leblanc and Ellis are correct, the Mimbres represent a different model of craft production in which specialists were not concentrated in one area, but spread throughout the society (Hegmon 2002). The earliest classification of the designs painted on the pottery was set forth by Jesse Walter Fewkes (1850-1930) in Designs on Prehistoric Pottery from the Mimbres Valley, New Mexico (1925). In this work, Fewkes divided the designs into three types; geometric, conventionalized, and realistic. Within these three types, Fewkes also identified a number of themes including: human figures performing various activities; the representation of multiple animals ranging from realistic to whimsical; and varied geometrical designs ranging in complexity. Although more extensive stylistic classificatory systems have been established since Fewkes’ simplistic model, the basic themes of human, animal, and geometric designs are well represented throughout the Natural History Museum’s collection. Though the images painted on the pottery are identifiable as human, animal, or geometric, their intended meaning remains a mystery. As J.J. Brody notes in Mimbres Painted Pottery (1977), regardless of the difficulty in interpreting the images, it is clear that “the paintings were made at the very least to commemorate the real or imagined existence of a being or thing.” In other words, whether or not the designs simulate reality or fantasy, the fact remains that, in terms of iconography, such images have the potential to illuminate the deceased Mimbres culture. Woosley and McIntrye note that “the painted pottery seems to voice more of a potter’s individuality and cultural connectedness through graphic expression”—suggesting that the artists creativity “ in terms of approaches to design layout, decorative motifs, and composition” could have largely determined images represented throughout the pottery (Woosley and McIntyre 1996: 205). Though there is no published study analyzing the designs as a whole, research focusing on certain categories of images have been attempted to better understand what is being portrayed. In fact, interpretations by Hopi people have been utilized in an effort to illuminate the significance of this imagery, (Hegmon 2002) In addition, artists and art historians have also offered their interpretations of Mimbres iconography, lending more diverse assumptions as to the significance of such imagery. Despite conflicting interpretations of the painted designs which exist throughout the archaeological and artistic worlds, the use of the pottery is less controversial. The majority of the bowls and pitchers were most likely made to be used in everyday subsistence activities; however, some archaeologist suggests they served a purely mortuary function (Brody 1977, Bray 1982) As Fewkes would discover in his excavations of the Oldtown and Osborn ruins, the deceased were buried in an upright crouched position with a bowl (often, but not always painted) placed over their heads. The decorated bowls were “killed” through the use of a sharp object, which served to pierce a hole in the bottom of the vessel (Fewkes 1914). Archaeologist J.J. Brody suggests that the act of piercing the bowl and placing it over the head of the deceased allowed the spirit of the dead to escape the body. Archaeology of the Mimbres Although Southwestern archaeologists were aware of sites in the Mimbres Valley, none were of particular interest because of the richness of neighboring Pueblo ruins. Nearby sites including Chaco Canyon, Cliff Palace, Mesa Verde, and Pueblo Bonito enticed countless excavations and publications, while the seemingly unimpressive and clearly uninhabited Mimbres sites were, for the most part, neglected. Despite brief publications by Adolph Bandelier, Clement Webster, and Walter Hough, the Mimbres Valley did not interest or inspire archaeologists until the 1920’s and 1930’s — years after Fewkes’ initial excavations at the Osborn and Oldtown ruins. Considered, perhaps, a precursor to the widespread excavations of the following decades, Fewkes’ trip and subsequent publications undoubtedly drew attention to the artifacts and culture of the Mimbres Valley. During the summer months of 1914, Fewkes toured the vicinity of Deming, New Mexico, the location of E. D. Osborn’s ranch, and the treasured pottery that had prompted his trip. What Fewkes found when he arrived was the aftermath of rudimentary excavations littered with pottery sherds and skeletal remains. Despite the desperate state of the sites, however, the unique designs on Osborn’s reconstructed pottery encouraged Fewkes to conduct his own excavations at Osborn’s ranch (ruin) and Oldtown ruin (Fewkes 1914). In the years following his first trip to the Mimbres Valley, Fewkes published three volumes: Archaeology of the Lower Mimbres Valley, New Mexico(1914), Designs on Prehistoric Pottery from the Mimbres Valley, New Mexico (1923), and Additional Designs on Prehistoric Mimbres Pottery (1924). Based on his final publication regarding the Mimbres pottery, it is clear that Fewkes returned only once in 1923 for the purpose of purchasing more of Osborn’s collection. Having accomplished the latter without further excavations, it follows that Fewkes’ final two publications were the result of further study and speculation of the collections accessioned by the U.S. National Museum. Although Fewkes passed away only six years after his final publication, never to return to the Mimbres Valley, research on Mimbres culture and pottery has persisted into the 21st century, constantly bringing new life and meaning to Fewkes’ collection here at the National Museum of Natural History. Text from: Smithsonian, National Museum of Natural History |